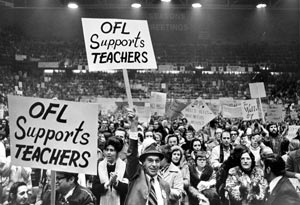

I have been constantly reminded of my own experience on the picket line as a young teacher. It was 1975 and I was in my second year teaching high school history in Toronto. Teacher salaries had been frozen by the province for the previous six years but finally, the purse strings had opened up a bit and we were at the bargaining table determined to make up for lost time and wages. On the other side was the Metropolitan Toronto School Board who were just as determined to keep any settlement within their budgetary reach. In October, we received a "Fact Finder's Report" (part of the Ontario bargaining legislation at the time) which recommended a 35% increase including a built in COLA clause. At a rally at Maple Leaf Gardens we chanted, 15,000 strong, that "the Fact Finder knows the facts" and we were assured by our union leaders that the Board's agreement to our demands was a "no brainer".

Meanwhile, the Board, faced with our righteous demand of 35%, had come to the table offering a paltry 32% increase. What an insult! At the same time, on the other side of the province, the federal government announced the introduction of Wage and Price controls (are you old enough to remember "Zap, you're frozen!"?) which would be applied to any settlements arrived at after October 31st. Our elementary colleagues quickly settled for the 32% and quietly went on teaching. We turned it down and, on Remembrance Day 1975, found ourselves on strike.

To add insult to injury, the weather immediately turned cold and snowy. Our time on the picket line was spent stamping our freezing feet and jumping back from showers of slush sprayed in our direction by passing cars. Like the teachers in BC, there was no money for strike pay and so we all took on part-time jobs - I drove a truck (my summertime job at university) and had the distinction of having my picture on page 2 of the Toronto Star over the quote: "Paid more as a trucker". I was quite proud of my 15 minutes of fame, while my mother was sure that I would be fired. At seasonal parties, my non-teaching friends told me how overpaid and underworked most teachers were ("Not you of course, Jim!) And we scrimped along on less than half of our usual income. Not everything during that time was bad. Camaraderie was high among me and my colleagues. We had lots of time for stories and socializing and we held on to the naive hope that in the end it would all be worthwhile.

For two months we pounded the pavement. Christmas was lean and January was even leaner. Finally (and thankfully) on January 16, 1976 we were legislated back to work with binding arbitration. The denouement to this time on the line was an eventual imposed settlement (32% - the exact same deal that the elementary teachers had accepted back in October) and a sense of shell shock. To make matters worse, the AIB (Anti-inflation Board) was good to its word and rolled us back a further 3 or 4%. At the end of the day, we received less than we had turned down months earlier and were out of pocket 20% of our year's salary.

That was my one and only strike as a teacher. I have weathered them as a Principal and Superintendent but from the other side of the table. Having said that, there were five important lessons that we all learned from those days:

1. Never believe your own hype. We teachers often live in a bubble and although we might have an iron-clad case for our demands we often fail to consider how the rest of society might view them (and us). Teachers often get lulled into thinking that their bargaining position (the starting point for negotiations) is going to be the end point of a settlement. Sometimes, as we learned the hard way, you just have take what you can get and regroup for the next time.

2. You are involved in a labour dispute not a crusade. I was bussed to Parliament Hill in the winter of 1975 to meet with government and opposition MPs and make our case against the involvement of the AIB in our dispute. They were polite but clearly wondered why we hadn't settled when the getting was good. They threw the cold water of pragmatism on our fiery idealistic demands.

3. Stay publicly united before, during and after the strike. Behind closed doors we quietly replaced the entire union leadership who had postured and recklessly misread both the economic times and the public mood in taking us out on strike. On the Board side, the same thing happened in subsequent municipal elections. As a result, a new more reasoned leadership emerged that was able to work positively towards solutions instead of practicing brinkmanship as a negotiating strategy. We teachers had little tolerance for those who told us it was "worth it" and yet had never given up even a single pay-cheque while we went penniless for months.

4. Never compromise your professional integrity. There were times during the strike when we wanted to lash out at the Board, at the media, and at a generally disinterested or mildly hostile public. These were the days before social media and so most of our feedback was from either thumbs up or middle fingers raised from passing cars. We took our lead from the Penguins of Madagascar - "Just smile and wave, boys."

5. When it's over, it's over. Go back to doing what you love, teaching kids. The first day back from our strike we had a staff meeting. The Principal announced that all Pro-D and exam days had been cancelled for the rest of the year to make up for lost instructional time. He then said something that I will never forget. He said that in any strike you start with "tools down". You stop working and walk off of the job. You end the strike and it's "tools up". You walk back in and throw yourself back into your job with all of the energy and professionalism that it, and your students, deserve.

It has been almost 40 years since I was that young teacher on the picket line. "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times", but ultimately it was not about governments and unions. It was about how each of us handled it as teachers, administrators and parents.

My advice to our colleagues on strike, when you finally walk back into that classroom, make everyone see the professional that you are and why you really deserve everything that you asked for, and more. The tenor of the school year, and the experience of your students after the strike, are what matters most of all.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed