Next Tuesday, school starts again. Actual, go to class, see your teachers, reconnect with your friends, kind of school. For those of us who have been haunting echoing halls and empty classrooms since last March, these are enervating and exciting times. Right now, the building is buzzing with activity. Rooms are being rearranged, organized and decorated to welcome everyone back, teachers and tutors are excited to reconnect with their students and even the various new systems and protocols that we are putting in place are not getting in the way of excitement and anticipation of next week's restart.

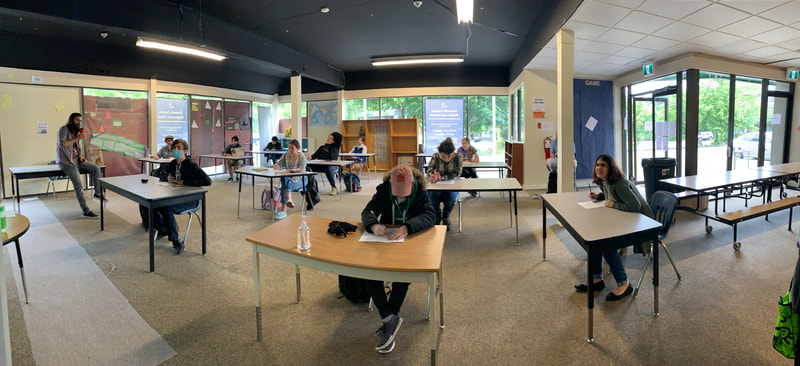

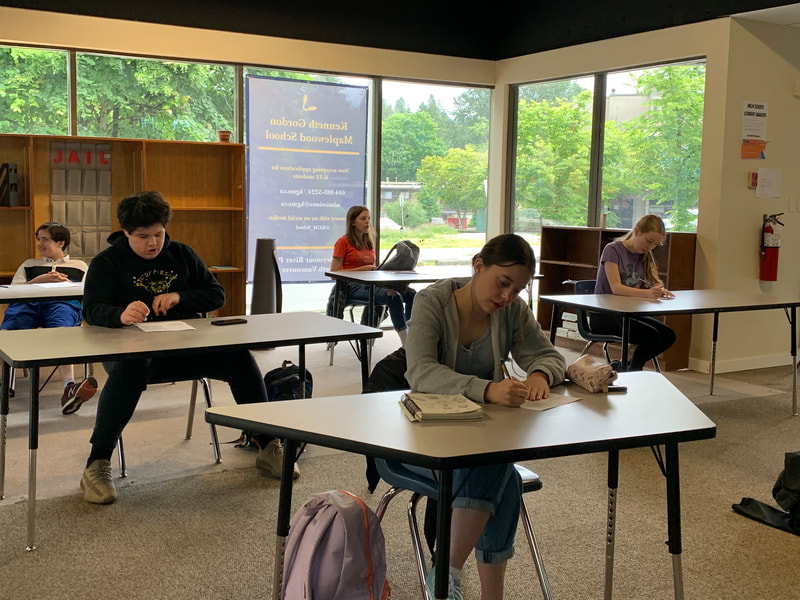

So what will the "new normal" look like? To be honest, as much as I groused about it at the time, our dry run in June (two weeks, voluntary, part-time attendance) both gave us great insights into how this can work, and noticeably lowered our collective angst about the prospect of all being here together again.

The routines that we established in June for health checks, hand-washing, and sanitizing surfaces and equipment seem much less daunting to re-establish now. In place of the smaller numbers we had to manage last Spring, this time we have our designated learning groups (or cohorts) to help us in the process of education and collaboration between and among students and teachers. We have organized our arrivals, departures, play spaces and even our washrooms to ensure safe, controlled and manageable interactions.

Will it be perfect? Not a chance. There will be glitches, unexpected complications, and moments of uncertainty as we tackle these new challenges. We have been fortunate at KGMS to have had a highly dedicated staff, and tremendously supportive parent partners to help shepherd our students through a time of great anxiety and abnormality for all of us. Next week we take a strong step forward to re-establish the routines, personal connections, and sense of community that we have all been missing.

So, as we head back, I want to express my gratitude: to our families, thank-you. None of us signed up for this, but that didn't stop you from stepping up and filling the gap the closing of our school left for your children; to our faculty and staff, to a person, you have been outstanding in your professionalism and dedication in the service of our kids as you made a complex series of transitions appear seamless and natural; and, finally, on a personal note, I have been incredibly fortunate to have been surrounded by an amazing leadership team who have worked through breaks, weekends and summer holidays so that we can be ready to welcome all of our students back next week for the beginning of a safe and productive school year. You have gone far above and beyond - and it has made a world of difference!

Let me close with a quote from Marquez's "Love in the Time of Cholera" :

"It was the time...without hurry or excess, when [all] were most conscious of and grateful for their incredible victories over adversity. Life would still present them with other mortal trails, of course, but that no longer mattered: they were on the other shore. ”

It's my belief that that shore is just ahead of us now and that our collective effort will get us there together.

See you next week!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed